In a recent international custody case for return under the Hague Convention, a mother asserts a defense her son is settled in the U.S. and shouldn’t be returned. But his grades are bad, he misses school, and his connections to his stepfather’s family come at the expense of his longer relationship with family in Brazil. After the trial court orders him returned to Brazil, will the appellate court reverse?

Boa Sorte

Both parents, and the child A.R., are all citizens and natives of Brazil. The parents were married in 2011, and lived in Belo Horizonte, Brazil (meaning “beautiful horizon” and pictured above). In 2016 they separated, and finally divorced in 2021. The parents shared custody of A.R., but A.R. lived with the mother. The mother then began a relationship with a man who immigrated to the United States.

The father signed a passport application that included a travel authorization permitting A.R. to travel outside of Brazil. The mother and A.R. then flew to Mexico, where they crossed the Mexico-United States border in 2022. She then applied for asylum.

Upon discovering the abduction, the father filed a petition to return A.R. to Brazil. The trial court in the U.S. found the father had met his prima facie burden to show A.R. was wrongfully removed from Brazil. Then, it rejected all the affirmative defenses the mother raised about consent, the now settled defense and the grave risk of harm. The Mother appealed.

Florida and the Hague Convention

I have spoken and written about the Hague Abduction Convention and international child custody issues before. The Hague Abduction Convention establishes legal rights and procedures for the prompt return of children who have been wrongfully removed or retained.

The International Child Abduction Remedies Act is the statute in the United States that implements the Hague Abduction Convention. Under the Act, a person may petition a court authorized to exercise jurisdiction in the country where a child is located for the return of the child to his or her habitual residence in another signatory country, so the underlying child custody dispute can be determined in the proper jurisdiction.

The Hague Convention applies only in jurisdictions that have signed the convention, and its reach is limited to children under 16 years of age. Essentially, The Hague Convention helps families more quickly revert back to the “status quo” child custody arrangement before the wrongful child abduction. The Hague Convention exists to protect children from international abductions by requiring the prompt return to their habitual residence.

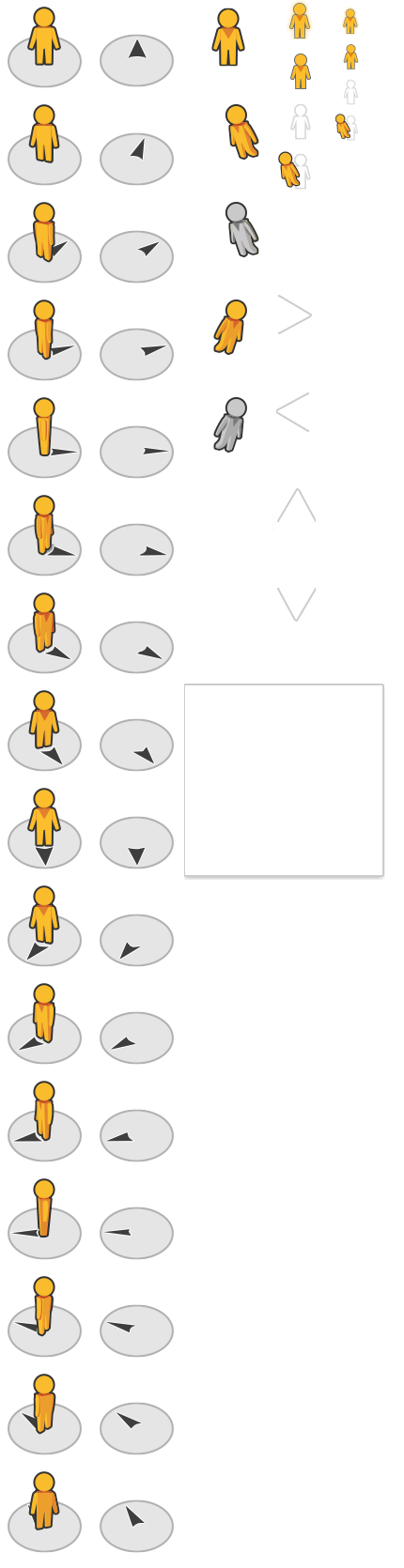

But there are defenses too. If return proceedings have been commenced after the expiration of a period of one year, courts can order the return of a child to their habitual residence, unless it is demonstrated that the child is now settled in its new environment.

Não Me Deixe Só

In rejecting the settled defense at the trial level, and ordering the child returned to Brazil, the district court analyzed several factors: age, stability and duration of the residence; whether the child consistently attended school; friends and relatives; involvement in the community and in extracurricular activities; employment and financial stability; and immigration status.

But on appeal, the circuit court found A.R. had lived in the same community for nearly three years, a significant amount of time for a school-age child. Also, his mother has steady employment and income. Those facts, standing alone, weigh heavily in favor of finding A.R. to be “now settled.”

A.R., it was also found, benefitted from a supportive extended family. He had a step-aunt and step-uncle who lived nearby and saw him twice a month. Despite A.R.’s poor grades and disruptive behavior, he arrived from Brazil unable to read or write in Portuguese, let alone in English, and was “meeting expectations of the classroom.”

The circuit court also found that A.R. attended church twice a month, participated in a youth group, had several friends of Brazilian descent, and importantly, played on a Massachusetts soccer team twice a week.

The circuit court remanded for the district court to decide whether, in the exercise of equitable discretion, returning A.R. to Brazil is warranted despite the appellate court finding that his status was “now settled.”

The case is here.